Bluetooth Covid Contact-Tracing Apps

In the previous article I looked at the tools the UK Government has available to deal with the coronavirus pandemic. Essentially, they have two. The first is to increase the number of ventilators and ICU beds, which gives more people with severe respiratory infections a chance to recover. That means that doctors and politicians can avoid the unpleasant choice of deciding who gets treated and who does not, but only if the number of infections are curtailed in the first place, so that we don’t run out of ventilators.

The second is the lockdown tool. It is currently a crude On/Off switch, which limits infections by keeping everyone at home. At the moment, it’s not flexible – you’re either locked down, or you’re not, unless you’re a key worker or in an essential industry. The hope is that few key workers will be infected, either because they have sufficient Personal Protection Equipment, or they’re able to social distance whilst doing their jobs. Everyone else has to stay at home. A lucky few can continue to work, but most are either furloughed or become unemployed, putting the economy in stasis.

The Government, quite rightly, is desperate to find ways to ease the lockdown. The question is how to do that without immediately seeing infection rates rise?

The flavour of the day is to roll out smartphone apps which can trace whether you have come into contact with someone else who is infected. The theory goes that if you do, you can be alerted and stay at home until you’re tested. If you have coronavirus, you self-isolate. If you don’t, you’re free to go back to work. Like many proposals for phone apps, it sounds simple, which is why it’s so appealing. Particularly to people like Matt Hancock, who has always had a bit of a penchant for phone apps, which he believes will save the NHS. What nobody is mentioning, is that for contact-tracing to work, we will need the ability to provide at least half a million additional tests that can be administered at home every day.

Before we look at whether contact-tracing phone apps will work, or how effective they might be, we should remind ourselves of the basics of virus transmission modes.

Transmission Modes

To understand the benefit of contact-tracing, we need to look at infection transmission modes, which is how we catch Covid-19. The current belief is that it’s almost always passed from person to person as a result of exhaled droplets from an infected person which we breathe in. There will be a small amount of environmental contact transmission from touching contaminated surfaces, but that’s likely to be minor. Most people will catch Covid-19 and show no symptoms for around a week, although they will be infectious during this period, which is the presymptomatic phase. As symptoms appear, they will realise they are ill and hopefully stay at home during the symptomatic phase, as they’re still infectious. Some of them will develop major respiratory complications, of whom a fair percentage will die. We don’t have a clear view yet of what that percentage is.

A small number of people will be asymptomatic. They will experience no symptoms, but will be infectious throughout. It’s currently thought that this is how many children experience it. That gives us the four transmission modes show below:

It’s important to state that we don’t know what the relative size of those four transmission modes are – this pie chart is based on a mix of inputs, but at this stage we are lacking sufficient hard data. If we did know the relative numbers, it would be much easier to plan a strategy, but the truth is we’re still at a very early stage of learning with Covid-19. We also don’t yet know whether you can catch it a second time. If you can, any bets on developing herd immunity as the exit plan are off.

There’s a well-established method of containing infections, which is isolating anyone who develops an infection, tracing their contacts, testing each of them and tracing their contacts if they’re infected. It involves a lot of manual work and a lot of testing, much of which will be negative. Governments around the world are hoping that the hard work can be replaced with a tracing app.

Asymptomatic infection is the most difficult to trace, as the person doesn’t know they have Covid-19. The only way we could find out would be to test everyone on a daily basis, which is around 60 million tests per day for the UK. That isn’t going to happen. So, we have to hope that the number of asymptomatic cases is low. If we can detect that someone has been close to a symptomatic person, we can potentially locate asymptomatic patients (if we have the resources available) but we can’t do much else about asymptomatic transmission.

The more common, symptomatic infection is the one which is used for tracing. At the point where someone thinks they have symptoms, they need to self-isolate and get themselves tested. If they test positive, that is logged in a central database, which can be made available to everyone running a contact-tracing app. Anyone who is flagged as having been in close proximity to anyone in that database within their infections period should isolate themselves and get tested. If they test negative, they can go back to work; if they test positive, they’re added to the positive contact data and need to stay isolated until they recover and are no longer infectious.

You can see why this works by looking at the diagram below. As soon as someone tests positive and is placed on the infected list, everyone who was in close contact with them can isolate and get themselves tested, whether they’re asymptomatic or presymptomatic. If they test positive, then they can isolate themselves throughout the infectious stage, saving everyone from the chance of catching Covid-19 from them. There will still be a lag because of the delay in testing the first symptomatic person, but we can significantly reduce the level of transmission for both symptomatic and asymptomatic infections.

There are some important things which need to be put in place for this to work. It’s critical to have fast, home testing, so that nobody should need to stay at home for more than 24 hours after they self-isolate. Otherwise we’re eating into the infectious stage of all of those people who have been near them and caught it.

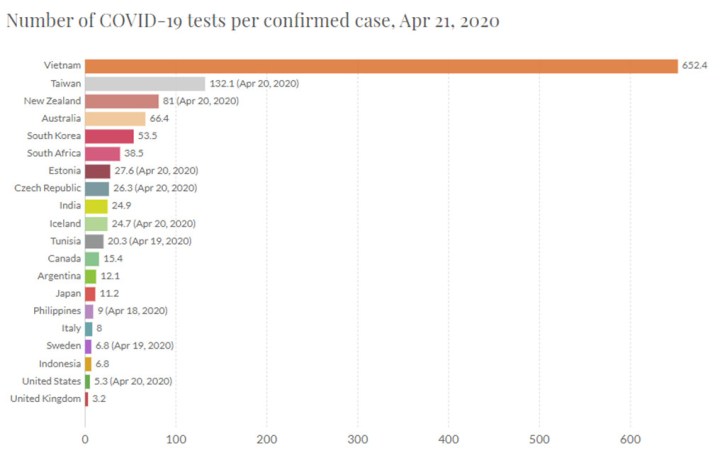

If your social distancing and tracing are working well, you will end up testing a lot of people – probably a hundred or more for each confirmed case. Taiwan is a good example, which is currently running around 130 tests for each confirmed case. In comparison, the UK is running just over three.

This testing is additional to what we need to do for frontline workers, (I’ll explain why in a minute). From these figures we can estimate how many additional daily tests would be needed in the UK to support contact-tracing. The Institute of Actuaries has calculated that the weekly deaths from Covid-19 in the UK were just over 8,000 in the week of 10th April, which is before we got to the peak. That’s just over 1,000 per day. The original epidemiology paper from Imperial College, on which Government strategy is based, suggests relaxing lockdown when numbers fall to around 20% of the peak, which will be around 200 deaths per day. If we take the WHO’s estimate of a 3.4% mortality rate, that equates to around 6,000 new infections each day across the country. (The estimates of mortality range from less than 0.1% to over 13%, largely because we’re not testing enough people.)

Let’s look at London to see what this means. At the moment we’re seeing 100 deaths each day, which means there are about 3,000 new infections each day, of which 2,900 people recover. If we exit lockdown at the point we reach 20 deaths per day, that equates to around 670 daily new infections. Each of these people will be presymptomatic and infectious for five days, meaning we can expect 3,000 infected people in circulation in London on any day after we end lockdown.

A tube carriage can hold 125 people (without social distancing) and a Bluetooth tracing app should pick up 50 – 100 of those during a journey to work. Add in the home journey and the people you come into contact with during your working day, and each of those infected people would be logged by at least 150 phones each day. Each day, around 600 should get to the symptomatic phase, experience symptoms, go home, self-isolate and get tested (I’m assuming around 10% are asymptomatic). By that point, they will have been logged by 750 phones (150 each day for 5 days). That results in 450,000 people being told that they may have been infected, should go home and be tested. There will be some overlap, but it means we’d need around half a million home tests performed every day to check they’re uninfected and able to go back to work. Otherwise tracing will send most of London’s 6 million workforce back home and will have inadvertently re-established lockdown within a fortnight. It means that a massive home-testing capability must be the priority.

Now let’s look at how we do the tracing.

Contact-tracing Apps

There are two main ways you can implement contact-tracing apps on a smartphone, either by monitoring absolute location, or by logging proximity to other devices.

Location tracking uses the GPS sensor on your phone to keep a record of where you are throughout the day. Most approaches send that data to a central, Government-run database which keeps a log of where everyone is. If those logs show that you came within a few metres of someone who has tested positive for Covid19, it will send you a message, telling you to go home and stay there until you’ve been tested. Someone then comes round with a home test kit and if you’re negative you can go back to work.

Proximity tracking is favoured by privacy advocates who don’t think that letting the Government log your every move is a good thing. It uses the Bluetooth Low Energy chip in your phone to send out low power messages which other phones can detect. Every smartphone using the app keeps a personal log of all of those contacts. That log is yours and it’s anonymised. Whevener you want, you can check your personal log against a Government database of people who have tested positive and your phone can work out whether you’ve been close to someone who has Covid-19. If you have, you go home, get tested, etc. The Government knows you’ve been tested and will file your test result, but they don’t have a log of your movements – that stays as your own, private information.

Each approach has limitations and issues. Location tracking using GPS doesn’t work on the tube, which is probably where most people in London will catch the virus. It doesn’t work well in buildings, which is the other place you’re likely to catch it. It will drain your phone battery faster than normal, and the Government will have a log of where you are at all times. On the plus side, the app is pretty easy to write, as developers have access to all of the GPS information they need through a standard phone programming interface.

Proximity tracking is more difficult, not least because Bluetooth Low Energy has been designed to be non-trackable, specifically to stop Governments and other malicious people from tracking you. Over the last few weeks, none of the apps developers who have contacted me appear to have realised that, although it’s clearly explained in the Bluetooth specifications, which means that the app proposals they’ve been submitting to the Government are unlikely to work. The good news is that Apple and Google, along with others in the Bluetooth industry, have come up with a standardised solution which can be deployed to most smartphones allowing these apps to work. It can also be turned off through a future firmware update, which gives a bit more confidence on the privacy front.

I won’t go into the finer details of privacy. Ross Anderson – an expert on security engineering at the Computer Lab in Cambridge has already written a thorough and very readable article on Contact Tracing in the Real World. He’s sceptical. Unfortunately, the Government is less so. There appears to be a desperation to be seen to be doing something, even if it doesn’t work. We can see that in their original ventilator specification, which was sent out to hundreds of manufacturers who had never made anything remotely like a ventilator. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency required that “they would be for short term stabilisation for a few hours, but this might be extended up to 1-day usage for a patient in extremis”. That’s a shorter working life than an ICU nurse’s hospital gown, and certainly not what they’d expect of something purporting to be a ventilator. It’s probably why the Government is now cancelling some of its previously lauded ventilator contracts and telling Dyson not to go ahead with its design. However, with the desperation to ease the lockdown, I doubt that much more scrutiny has gone into the specifications for the tracing apps.

Now we’ve covered the basics of transmission modes and tracing apps we can look at the real world to see whether the theory can be put into practice. In other words, would these apps work?

There is absolutely no doubt that we need to be able to change lockdown from its current binary states of On or Off. If we don’t get more people back to work, we cannot pay for a lockdown that could last two or three years. A vaccine is still no more than a hope and should not even be part of an exit plan. Despite massive research efforts for diseases like Ebola, we have never managed to achieve a reliable vaccine in much less than five years. We can scale up manufacturing capability and encourage more companies to develop them, but the proof of success is only when you vaccinate people and:

1. They don’t die (we shouldn’t forget the TeGenero TGN1412 trial), and

2. They don’t contract Covid-19

Getting both right is surprisingly difficult. But that won’t stop optimistic press releases as vaccine developers take the opportunity to secure funding or inflate their share price. Government ministers should be experienced enough not to put any credence in them. I hope we get a vaccine faster, but a vaccine is the fairy at the bottom of the garden, not an exit plan. We need to plan for the case where it doesn’t arrive.

Contact-tracing Apps in the real world

So, back to contact-tracing apps. If they are going to play a useful part, a significant proportion of the population needs to use them. Or rather “it”, as they need critical mass, so a nation really needs to decide on one app, rather than a raft of competing ones. To see how many people might be able to use one, we can start with figures from the Office of National Statistics for people with smartphones and internet connections. (I’ve added in further numbers from Statista and Childwise to fill in some gaps.)

It shows that from 11 to 54, most people in the UK have a smartphone with an internet connection. Overall, just over 48 million people are in that category, accounting for 73% of the population. Usage tails off quite rapidly as we move into the higher risk age groups.

That doesn’t necessarily tell us whether people would download and use the app, but here we have some data from Zoe, a healthcare company that have developed the popular COVID Symptom Tracker app. They have around a million users and have analysed the age of their app users. In general, the numbers are a close match to the ONS ones, except for the 20-30 age group, where Zoe only see half the expected usage.

That blows a hole in the widely held assumption that millennials would be the most likely to use a contact-tracing app. It’s possibly the most interesting piece of data to come out of the COVID Symptom Tracker. During a previous flu epidemic, the Lancet reported that there was a “growing tendency among the better educated classes to regard the epidemic as something almost too trivial for serious consideration”. Nothing much seems to have changed since they wrote that in 1890, other than the expectation of apps developers that their apps are relevant.

Of the 73% of the population with smartphones, how many will be able to use the app? To do so they will need the latest Apple / Google Bluetooth firmware. For iPhone owners, that should happen automatically. Over 90% of iPhones in the UK run the latest iOS version. For Android, it’s a very different story, with only around 15% of phones running the latest version. The fragmented manufacturing base for Android means that most of the Android devices on the market won’t get the update, so only around 52% of UK smartphones phones would be able to run Bluetooth contact-tracing software. Remember that not everyone has a smartphone; once you factor that in, only 38% of the population will have a smartphone which is likely to be updated to be able to run a Bluetooth contact-tracing app.

The numbers get worse when you ask how many people will actually run these apps. In some countries, such as Singapore and China anyone who wants to go out has to, which is a pretty powerful incentive. Although there may be very positive incentives to do so here, it’s unlikely the take-up will be much above 50%. That takes us down to just 19% of the population running the app.

There’s a good paper on the need to get widespread coverage from Oxford University, which makes the point that if it is going to be useful it needs to be used by enough people. That paper has an interesting sting in its tail, which is that certain groups, such as health workers, may need separate arrangements. In other words, they wouldn’t be expected to use these apps.

Whilst that may feel counter-intuitive, a few moments’ thought shows it’s not. Almost every front-line NHS and care worker will come into contact with an infected person during their day’s work. If they were all to stop work as soon as their phone pointed out that obvious fact, we’d have no health service. If we just remove the 3.0 million NHS and care workers from the number of people using the app, we’re down to just 14% of the population using the contact-tracing app. That is still a useful number, but it’s rather different to the near 100% that the Government announcements are implying.

How does this map this onto the working population? I couldn’t find any detailed numbers on how the lockdown has affected the working population, so I’ve taken the ONS dataset for employment and attempted to break down each of the 100 employment categories into Frontline workers, Essential workers, people working at home and those in Lockdown (either furloughed or unemployed).

To get the economy back up and running, the priority is to bring the Locked Down back into work without starting a further increase in the level of infections. Those working at home should be encouraged to continue to do so, which probably means schools need to reopen. More jobs can be moved into the Essential category, but that doesn’t address the enormous rump of retail, leisure, travel, entertainment and restaurants. To reopen that sector of the economy will need something to give people confidence to resume their pre-Lockdown lifestyles and it’s not clear that simple contact-tracing apps will deliver that. It is far more likely that the availability of mass testing will be needed. I don’t have an easy answer, but it is likely that we need to work on a far more nuanced approach, rather than the gung-ho attitude of “I’ve got a contact-tracing app which will solve everything”. Today we heard that NHSX – the digital tech wing of the NHS, is testing a contact-tracing app at RAF Leeming. Matt Hancock donned his rose tinted flying goggles to tell the House of Commons that “the more people who sign up for this new app when it goes live, the better informed our response will be and the better we can therefore protect the NHS”, missing the point that this isn’t about protecting the NHS, it’s about getting people back to work. And as we’ve seen above, that number is limited.

Our politicians appear to be taking comfort in rekindling a wartime spirit that brings everyone together, but this is not a boy’s adventure story. Many people will die as a result of this pandemic and responding in the wrong way will mean that more people die than need to. It may be that the best approach is to start with old-fashioned, personal contact tracing and then see how we can add phone apps to make it more efficient.

It is understandable that there is a political desire to be seen to be doing something, but the ventilator fiasco demonstrates that it is useful to think things through first. Tech by itself rarely solves a problem, not least because it has a habit of offering a solution before anyone bothers to ask what the question is. Smartphone Apps can be especially distracting, as the apparent ease of creating them, allied to the industry’s design maxim of “fail fast, learn fast” plays to the political knee-jerk reaction that favours short term thinking and a love of shiny things.

In the world of Covid-19, each wrong turn is probably going to push up the number of deaths. Contact-tracing is an important tool, whether or not it uses a Bluetooth app, but it will require the provision of an additional 500,000 home-administered tests every day. That provision has to come first. It’s a bit like writing a play. You need to start with the major characters – the Mark Antonys and Brutuses, not the spear holders, however glamourous and shiny their props may be. In the Covid-19 drama, the main characters are testing, testing and testing. Bluetooth contact-tracing probably has a part to play, but it’s a minor one in this story.

Let’s not get distracted by the tech. We need to think first and code later.

We need to think first and code later.

What a brilliant well balanced and informative article. I despair at the failure of politicians to understand science and engineering. How could anyone think you could ‘knock up’ a design and mass produce ventilators in a few weeks

Oh that’s even worse … if actual device BT controller firmware updates are required that would mean each individual device manufacturer creating an update for each handset model and then working with each mobile operator to approve and release the updates.

In that case I’d be surprised if we got to a low single-digit percentage of Android phones updated even in the next six months.

Thanks. I was given that figure as indicative of the number which would receive updates for Bluetooth firmware, which would be necessary if you’re implementing controller level duplicate filters. As that’s hardware specific, I wasn’t sure it would be available through Google Play Services. I’d be very happy to be proven wrong in that.

“For Android, it’s a very different story, with only around 15% of phones running the latest version. The fragmented manufacturing base for Android means that most of the Android devices on the market won’t get the update”

This is perhaps incorrect. Android main versions do not get updated on handsets often, if ever. However, updates can be pushed out via Google Play Services to pretty much all devices less than a few years old, which is likely how Google will do this.